Electric vehicles - second thoughts on secondhand

I'm on the hunt for a new car ... well, new to me. I've never actually bought a brand-new vehicle since passing my driving test. It just never really seemed worth it. As long as it gets me and the people I care about from A to B safely, I'm happy. I'm not too fussed about fancy features. Sure, the safety tech gets better over decades, but year to year? Not a huge difference. Okay, sometimes I need an adapter to charge my phone, and Bluetooth can be a bit bonkers. But, the trade-offs are worth it for the money saved.

New cars are expensive to build and to buy. But it's broadly accepted that if you buy a 3-year old car secondhand it'll be around 60% cheaper - what a win! It's one of my favourite forms of voluntary wealth re-distribution in modern society. This approach has held true for me for 20 years... but now I've moved to Norway.

A new way for Norway #

Norway decided that by 2025 all new passenger cars sold should be zero-emission. To make this happen, they unleashed a bunch of incentives. And it worked. These days, charging infrastructure is everywhere. Homes have electric vehicle (EV) chargers as standard, energy suppliers sell gizmos to optimise EV charging schedules based on electricity spot price, and (anecdotally) it's easier to find a charging port at a petrol station than petrol. As of 2024[1], 9 out of every 10 new cars sold were electric.

Looking at all the vehicles on the road, 2024 registration data[2] (Table 1) shows that 27% of all private vehicles are now electric:

Table 1. Private vehicles registered in Norway in 2024, by fuel type.

| Diesel | Electricity | Petrol | Gas | Paraffin | Other fuel* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 998,104 | 740,728 | 713,246 | 157 | 3 | 344,504 |

If you're reading this, you'll probably agree that these stats are pretty exciting 🤓. More EVs on the road means more secondhand EVs for cheapskate penny-wise people like us, right? Right?

The big scrapheap in the sky #

Let's talk about death. My subconscious world view was that vehicles lived for about 20 years. I was almost right; looking at some Norwegian stats (Table 2) we see that a typical vehicle gets scrapped at an average age of 18 years.

Table 2. Average age of private vehicles scrapped in Norway

| Year Scrapped | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Average Age (years) | 18.4 | 19.2 | 18.1 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 18.2 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 18.2 | 18.8 |

Okay, fine. Cars get scrapped - but as of 2025 most of those are petrol/diesel. Apparently EV's are a different beast. A friend who bought a brand new EV mentioned something that stuck with me:

"When the battery dies, it's time to get a new vehicle."

Why get a new vehicle? Well the battery accounts for about 30% of the vehicle cost - so replacing it at the end of life[3] is probably more than the car is worth. That begs the question: "when will the battery die?" Well, The US National Renewable Energy Laboratory reckons EV batteries will last[4] 12-15 years in moderate climates, but only 8-12 years in extreme climates. I'm in Southern Norway - we have mild summers, but winters get pretty chilly. So I'm hoping for about 10 years before the battery reaches "end of life".

"What's the end of life?" I hear you asking. EV batteries are considered "end of life" when they hit 80% of their original capacity. That happens after about 4,500 charging cycles. If you're anything like me you're thinking: "well, 80% isn't that bad. If the initial range is 400km, then it'll degrade to 320km, right?" Nope. After the 80% point the capacity starts to exponentially decay and the battery is just not reliable enough to power an EV.

So, 4,500 charging cycles is about 10 years of daily charging. 10 years is about half of my feel for a vehicle lifetime... so I need to revisit the geekery I use to find a good deal. But first, let me introduce my algorithm.

Car buying autopilot #

A while ago I put together a 2-stage algorithm to help me pick a good value secondhand car. First up calculate a fair price for the vehicle based on how used up it is.

Where

The end result is pretty straight forward... the higher the

This worked well for petrol cars in the UK. I'd filter for cars under 10 years old, with 5-star Euro NCAP ratings, crunch the numbers, and boom, secondhand bargains. So, I took that goodness, and applied it to my Norwegian EV hunt.

What the fjord? #

On the hunt for my secondhand bargain, I pulled together all vehicles that met my age and safety criteria in Southern Norway. This gave me 2,420 vehicle ads from finn[5] - the dominant Norwegian secondhand sales platform. I then grabbed the sticker price for each vehicle (thanks tax office) and plugged the details into my algorithm.

When I calculated the

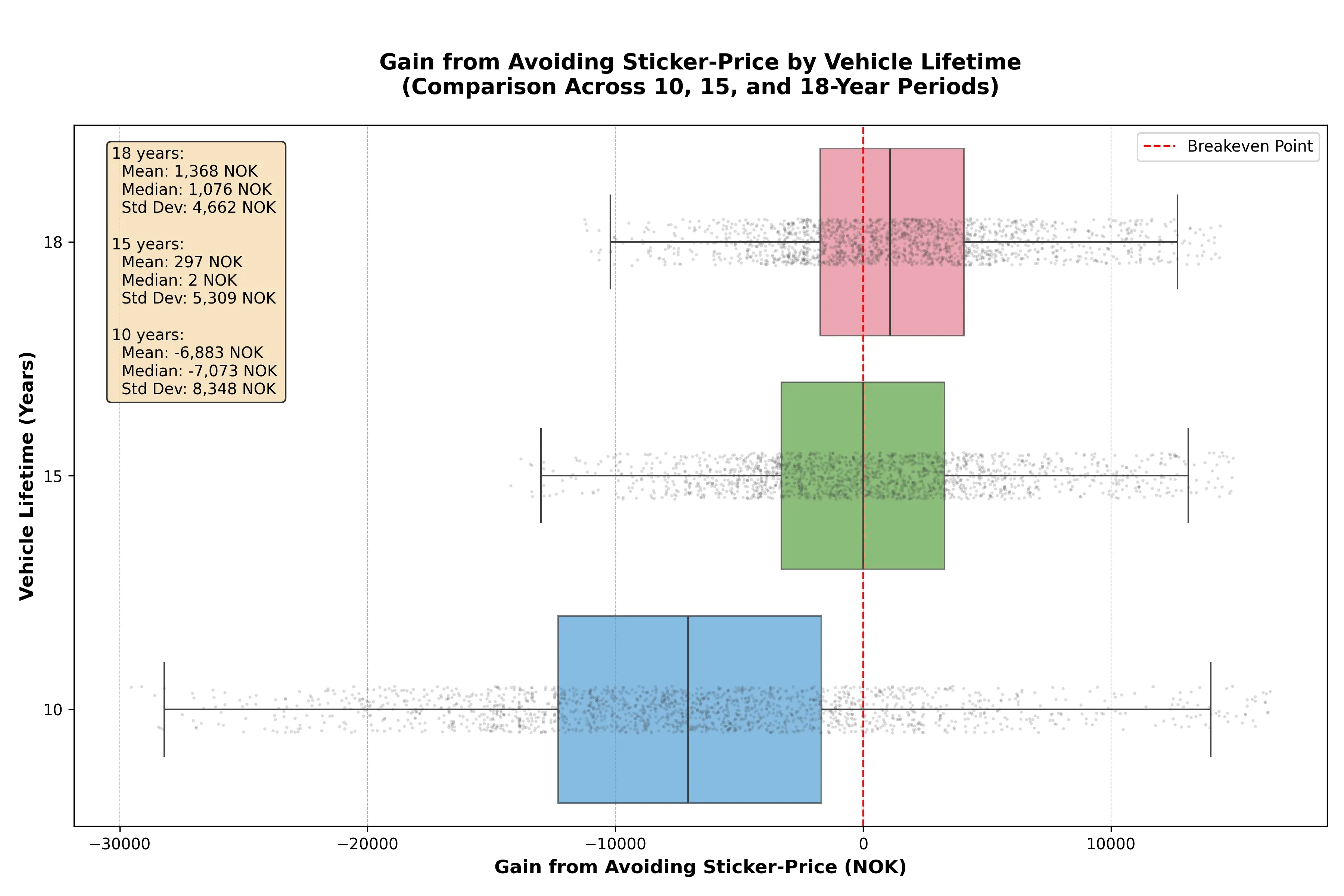

Figure 1. Gain from Avoiding Sticker-Price for an EV

If EVs only last 10 years (i.e. the expected life of a battery), the average used EV actually costs you an extra 7,073 NOK per year compared to buying new. You'd need the car to last 15 years just to break even, and only start saving money if it lasts 18 years - which happens to be the average age when cars get scrapped in Norway.

I know what you're thinking - nice boxes in Figure 1, but what does it mean? Well the short version is that (assuming a 10-year total lifespan) buying a secondhand EV in Norway typically COSTS you an extra 7,073 NOK ($700 USD) per year compared to buying new. I re-ran the algorithm and found that you'll break even (i.e. pay the same as someone who bought it new) with a total EV lifespan of 15 years. However, running the algorithm again with an assumed lifespan of 18 years shows something I'm more familiar seeing for petrol cars - bargains in the secondhand market.

So, in short, it looks like the secondhand market is pricing EVs as if they'll last 18 years, like petrol cars, while science and economics say they'll be a writeoff in 10 🤦.

Second chance for secondhand #

Figure 1 paints a pretty clear picture: the secondhand EV market in Norway is, on average, totally bonkers. But, if you filter out the 77% of listings where

What really rubs salt in the wound is that the best bargains tend to show up at the higher price points. Once you dip below 300,000 NOK, the pickings get slim. The percentage of bad deals is still high, but even the good ones don't offer as much value, the

Figure 2 shows the best secondhand EV deals across Southern Norway at the time I pulled the data. If price isn't an issue, there's an decent deal on a Mercedes-Benz EQB 250, you'd get about 8 years of driving, and you'd definitely be saving a ton compared to buying new.

But if you set a cap at 300,000 NOK (that still feels like a lot for a used car), the situation changes. The

Figure 2. The best

🏆 Best Value Secondhand EVs 🏆 ============================================================= #1 - MERCEDES-BENZ eqb 250 (2023) 💰 Asking Price: 412,343 NOK ⚖️ Fair Price: 1,047,044 NOK ✅ Good Deal by: 634,701 NOK 📊 Bargain Score: 2.54 (Higher is better) 💸 Original Price: 1,135,000 NOK 🛣️ Mileage: 13,905 km | 🔋 Effective Age: 2 yrs 🔗 View Ad: https://www.finn.no/mobility/item/410371819 ------------------------------------------------------------ #2 - AUDI e tron gt (2023) 💰 Asking Price: 689,000 NOK ⚖️ Fair Price: 1,271,962 NOK ✅ Good Deal by: 582,962 NOK 📊 Value Score: 1.85 (Higher is better) 💸 Original Price: 1,592,200 NOK 🛣️ Mileage: 32,000 km | 🔋 Effective Age: 2.0 yrs 🔗 View Ad: https://www.finn.no/mobility/item/407981487 ------------------------------------------------------------ #3 - AUDI q4 45 e-tron (2024) 💰 Asking Price: 469,900 NOK ⚖️ Fair Price: 863,305 NOK ✅ Good Deal by: 393,405 NOK 📊 Value Score: 1.84 (Higher is better) 💸 Original Price: 934,900 NOK 🛣️ Mileage: 22,000 km | 🔋 Effective Age: 1.0 yrs 🔗 View Ad: https://www.finn.no/mobility/item/411348294 ...

🏆 Best Value Secondhand EVs (under 300,000 NOK) 🏆 ============================================================= #1 - OPEL corsa (2023) 💰 Asking Price: 197,343 NOK ⚖️ Fair Price: 293,972 NOK ✅ Good Deal by: 96,629 NOK 📊 Value Score: 1.49 (Higher is better) 💸 Original Price: 323,900 NOK 🛣️ Mileage: 15,255 km | 🔋 Effective Age: 2.0 yrs 🔗 View Ad: https://www.finn.no/mobility/item/400298604 ------------------------------------------------------------ #2 - XPENG g3i (2023) 💰 Asking Price: 269,343 NOK ⚖️ Fair Price: 342,516 NOK ✅ Good Deal by: 73,173 NOK 📊 Value Score: 1.27 (Higher is better) 💸 Original Price: 372,300 NOK 🛣️ Mileage: 4,100 km | 🔋 Effective Age: 2.0 yrs 🔗 View Ad: https://www.finn.no/mobility/item/410754434 ------------------------------------------------------------ #3 - JAGUAR i-pace (2021) 💰 Asking Price: 273,434 NOK ⚖️ Fair Price: 347,328 NOK ✅ Good Deal by: 73,894 NOK 📊 Value Score: 1.27 (Higher is better) 💸 Original Price: 628,950 NOK 🛣️ Mileage: 48,500 km | 🔋 Effective Age: 4.0 yrs 🔗 View Ad: https://www.finn.no/mobility/item/410992857 ...

The whole situation leaves me caught between a rock and a hard place. With secondhand EVs, it seems you typically get less than you pay for. It's almost always a false economy at the entry level EV price points. In fact, it's a freaking textbook example of the boots theory of socioeconomic unfairness[7] i.e. if you can afford a new or high-end used EV you get a solid deal, but if you're on a tighter budget, you end up overpaying for something that might not last. Not cool.

The Final Verdict #

My 20-year strategy of buying secondhand cars has hit a speed bump. The EV market clearly hasn't settled yet, and for bargain-hunters like me, the pickings are a lot slimmer than they were for petrol vehicles.

Maybe this is just part of the transition. Give it a few years, and as more EVs reach the end of their first life, the secondhand market might start pricing things more sensibly. Or maybe battery tech will leap forward and make all of this irrelevant.

In the meantime, I'm stuck choosing between three equally unsatisfying options: betray my lifelong penny-wise values and buy new, overpay for a secondhand EV and try not to think about it, or lean into my eccentricity and embrace a bicycle lifestyle: trailer attached, dog in tow, attempting winter adventures across Norway's icy switchbacks and wildly vertical geography.

Whatever I choose, two things are clear: car buying in Norway is waaaay complicated, and it definitely costs more than it ever did in the UK.

Footnotes

Their stats are paid-for and (as is probably clear from the article) I'm cheap, so I just trusted the media reports of them and hoped they were interpreted correctly... ↩︎

Both new and secondhand vehicles get "registered" when they get a new owner, accounting for the discrepancy with new vehicle sales. ↩︎

Given the pace of EV battery development I'm not sure it's safe to assume that a given EV manufacturer will still be making the parts / batteries required for replacement. ↩︎

The main culprits behind battery degradation are temperature, discharge current, charge current, and depth of discharge. When you're buying used, you're basically trusting the onboard battery health indicators since you don't know how the previous owner treated it. If you want the full technical deep dive, check out https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3271287. I sourced the NREL study from the US Department of Energy which references a predictive model https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy14osti/62813.pdf. A quick google search shows there's some controversy about EV battery lifetimes. To settle the argument I suspect the scrapping stat will be the most important one to watch (in Norway) over the next 20 years. ↩︎

I added a few search parameters to filter out vehicles that were either not secondhand, or were attempting to resell a leased vehicle. I also narrowed it down to the kind of vehicle I'm looking for - i.e. in South Norway as the vehicles are less likely to be worn down by weather, and range of 400km or more. ↩︎

I've put quite a bit of work into tweaking the model to make the fair value numbers actually meaningful. Imports, for instance, get dinged a bit, it's harder to track their maintenance history, and some of them have spent years marinating in road salt. Not ideal unless you're into crunchy undercarriages. ↩︎

If that's new to you, the idea goes something like this: a rich person can afford to buy a pair of high-quality boots that last ten years, while a poor person has to buy cheap boots that fall apart every year. Over a decade, the poorer person ends up spending more. ↩︎